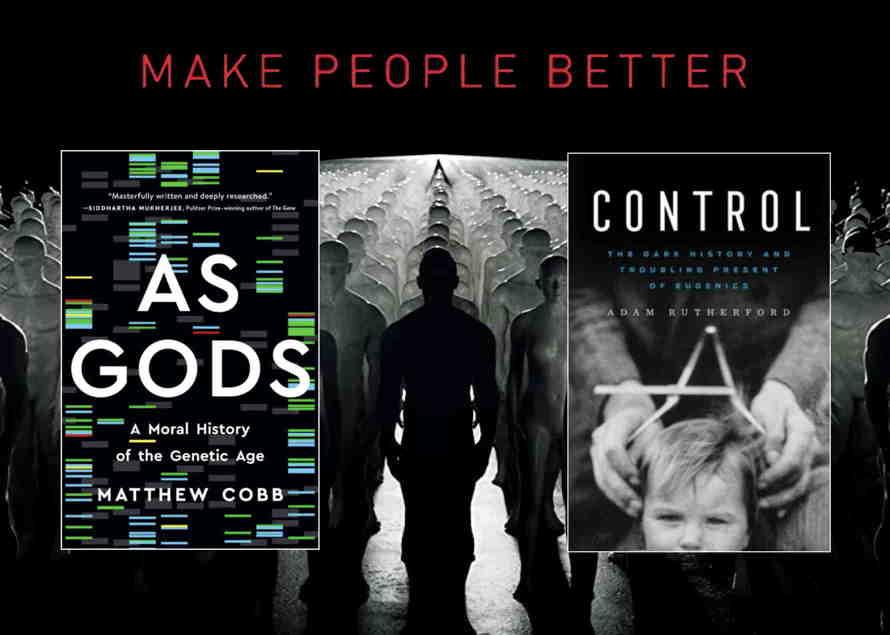

Techno-eugenics: Two Books and a Movie, Reviewed

Matthew Cobb, As Gods: A Moral History of the Genetic Age, US edition, Basic Books, 2022; aka The Genetic Age: Our Perilous Quest To Edit Life, UK edition, Profile Books, 2022

Adam Rutherford, Control: The Dark History and Troubling Present of Eugenics, UK, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2022; US, W.W. Norton, 2022

Make People Better, Documentary about He Jiankui, Directed by Cody Sheehy, streaming at Amazon, iTunes, YouTube, etc, 2022

Two books and a documentary, all released in the US in late 2022, join the growing ranks of accessible and authoritative accounts of the prospect of human genetic modification. The common thread among these projects starts with He Jiankui, the Chinese scientist who notoriously edited (sloppily) three human embryos and arranged for them to be used to initiate pregnancies. He announced the births of two resulting babies in November 2018, provoking global outrage. The film is entirely focused on the He Jiankui episode, and He shows up on page 2 of both books, though Cobb and Rutherford essentially use his case as a hook for much broader discussions.

1

Cobb’s As Gods is a well-researched, carefully annotated account of the development of theoretical and practical genetics over the last half century. The unfortunate title of the US edition is the publisher’s fault, though Cobb did name the penultimate chapter “Gods?” – and proceeded to debunk grandiose claims about de-extinction, genetic art, fluorescent fish and similar “tiresome crap.” The US subtitle is also misleading, as the book is not really a moral history either, though it is about the “perilous quest to edit life” and in particular how scientists have tried, with some success, to claim authority over decisions as to what applications of genetic engineering should be allowed.

These debates among scientists can be traced back to a 1974 call by Paul Berg and ten other prominent scientists to suspend work on recombinant DNA until they were sure it was safe. This led to the paradigmatic Asilomar conference of 1975, which to this day is cited as a triumph of scientific self-regulation. Cobb rightly situates it in the tumultuous politics of the era, and notes that of the 140 attendees only four were women and none were Black. Ethical and legal questions got short shrift (one hour near the end). Senator Edward Kennedy complained that the scientists were making public policy “far beyond their technical competence” and Cobb notes that “a tiny elite was taking decisions for the whole planet.” Moreover: “From the outset, the fundamental objective of the organisers was to agree the conditions under which experimentation could recommence.” Plus ça change …

The book covers an enormous amount of ground, and overall does it well. There are of course a few minor errors or omissions but this is definitely one for the reference shelf. The author is, in general, “enthusiastic about [the] technology” – but regards human heritable gene editing as “pointless and foolish” and quotes approvingly two different experts suggesting that these novel technologies tend to be “solutions in search of problems.”

In an interview published by Undark, he went further, calling pre-implantation selection “soft eugenics, voluntary eugenics” that won’t work anyway, in particular for “intelligence, or blue eyes, or whatever”:

Don’t waste your money, is my very strong advice. You can’t do this in the U.K.; it’s completely illegal. But in the U.S., you can do this. And you shouldn’t do it, for the very simple reason that the characteristics that they’re promising, they cannot deliver on.

2

Rutherford’s Control is a more focused but just as useful contribution. It is divided into two: Part One, sardonically titled “Quality Control,” is a history of eugenics in 122 pages, from Ancient Greece to Nazi Germany, after which it was thought to be all over. Part Two is “Same As It Ever Was,” and demonstrates quite clearly that eugenic impulses not only still exist but are being deliberately promoted by people who surely ought to know better.

Rutherford very clearly demonstrates the similarities between old-fashioned Galtonian eugenics and modern attempts to monetize trait selection in embryos, and possibly even edit them. He also offers a subtle and sensible discussion of attempts to reduce or eliminate Down Syndrome, for example, or Huntington’s. The author insists that he is not advocating a particular view, but of course to an extent he is:

Informed, compassionate choice should be enshrined in these extraordinarily hard decisions.

To ram the point home, Rutherford points out how great society’s loss would be had various talented people been screened out of existence. He cites as examples the great songwriter Woody Guthrie, who was affected by Huntington’s; the actor and comedian Robin Williams, who was bipolar and had Parkinson’s; the wheelchair-using physicist Stephen Hawking; the manic-depressive composer Ludwig Beethoven; the wide-ranging genius Isaac Newton, who may have been schizophrenic … possibly even Francis Galton himself, the man who named eugenics but is said to have been extraordinarily anti-social. Rutherford’s summary:

Those who ponder a new eugenics, or embryo selection for things like intelligence, or set up companies to sell this service, they are careless people – as The Great Gatsby’s narrator says – people who say things easily and let others clear up the mess they make. Scientists cannot afford to be careless, and no one can afford to be careless when creating new people.

Careless is exactly what He Jiankui was, Rutherford notes. He was careless of legal niceties. He was careless of the effect of his attempts at editing embryos – he knew the modifications he made were not entirely successful but went ahead with the pregnancies anyway. He was careless of the fact that at least one of the embryos he implanted was mosaic, that is, had different DNA in different cells. Rutherford delineates these “moral and legal violations” and notes that the technical issues were not surprising.

3

He Jiankui is the central subject of the documentary titled Make People Better. Not exactly a hero, not entirely a villain, JK (as he is widely known) was ambitious and determined to make his mark. He saw himself as a pioneer pushing boundaries, who would be seen as a courageous hero, a historic figure like Robert Edwards, who faced down criticism and eventually won a Nobel Prize “for the development of in vitro fertilization.” It also seems clear that the largely self-selected, mostly English-speaking mainstream community of genetic scientists was very quick to throw him to the wolves. Harvard Professor George Church, a prominent member of that community who was not close to JK and by all accounts did not know what he was doing, later commented that “He had an awful lot of company to be called a ‘rogue’.”

The title, according to JK, comes from James Watson, introduced in the film as a “towering figure in molecular biology” (which was true 70 or even 20 years ago, not so much now). As a credentialed scientist working on using CRISPR technology to edit human embryos, JK had been invited by Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna to a 2017 meeting in Berkeley attended by Church and other notable scientists, including Watson. JK asked Watson if genetically engineering people was a good thing to do, and says the reply consisted of the three words that became the film’s title. That advice, JK told bioethicist Ben Hurlbut, gave him “the courage to be the person to break glass.”

Hurlbut met JK at that meeting, and is featured throughout the film, interviewing the disgraced scientist by phone several times and also providing commentary. He notes that “JK was brought into an inner circle of people who were at the vanguard of the area that he was trying to break into.” Some of them soon either suspected or knew what JK was planning, namely to edit embryos with the specific goal of making them resistant to HIV (a move that few considered medically compelling). William Hurlbut, Ben’s father, a Stanford bioethicist who would have been a valuable witness for the movie, apparently knew what JK intended to do but not that he had actually done it. Biologist and Nobel Prize winner Craig Mello actually did know about at least one of the pregnancies JK started, but explicitly asked not to be informed of its progress, writing in an email to JK (reported by the Associated Press in 2019 and not included in the movie): “You are risking the health of the child you are editing … I just don’t see why you are doing this.”

When the news of his reckless experiments broke in late 2018, the reaction of most distinguished scientists was reminiscent of the famous scene near the end of the movie Casablanca in which Captain Renault is handed his winnings moments after having closed down the nightclub for illegal gambling: They were shocked, shocked to find that editing had been going on here.

Reporter Antonio Regalado, who scooped JK by breaking the story shortly before the planned announcement, commented: “Technology’s a great way to make money. You have control, molecular control, over the makeup of the human body. Molecule by molecule. It’s worth a ton of money.”

That could have been part of JK’s motivation – there are reports he planned to open a clinic or partner with an established clinic to commercialize genetic-enhancement technology. The movie is vague on that point, but does leave the impression that He was scapegoated for trying to do what more mainstream scientists are planning on doing themselves. It could be interpreted as suggesting that in the eyes of the scientific luminaries who have taken charge of a highly visible set of deliberations about heritable genome editing, He’s real sin was jumping ahead of their own carefully orchestrated timeline.

Immediately before the credits, slides go up on the screen, saying:

Scientists continue to develop this technology.

Time Magazine listed JK as one of the “100 most influential people of 2018.”

Thirteen months after his disappearance,

the Chinese government sentenced JK to three years in prison.

The location and health of the babies remains a mystery.

This story is almost certainly not over.