Talking Biopolitics: A Conversation with Tina Stevens and Stuart Newman

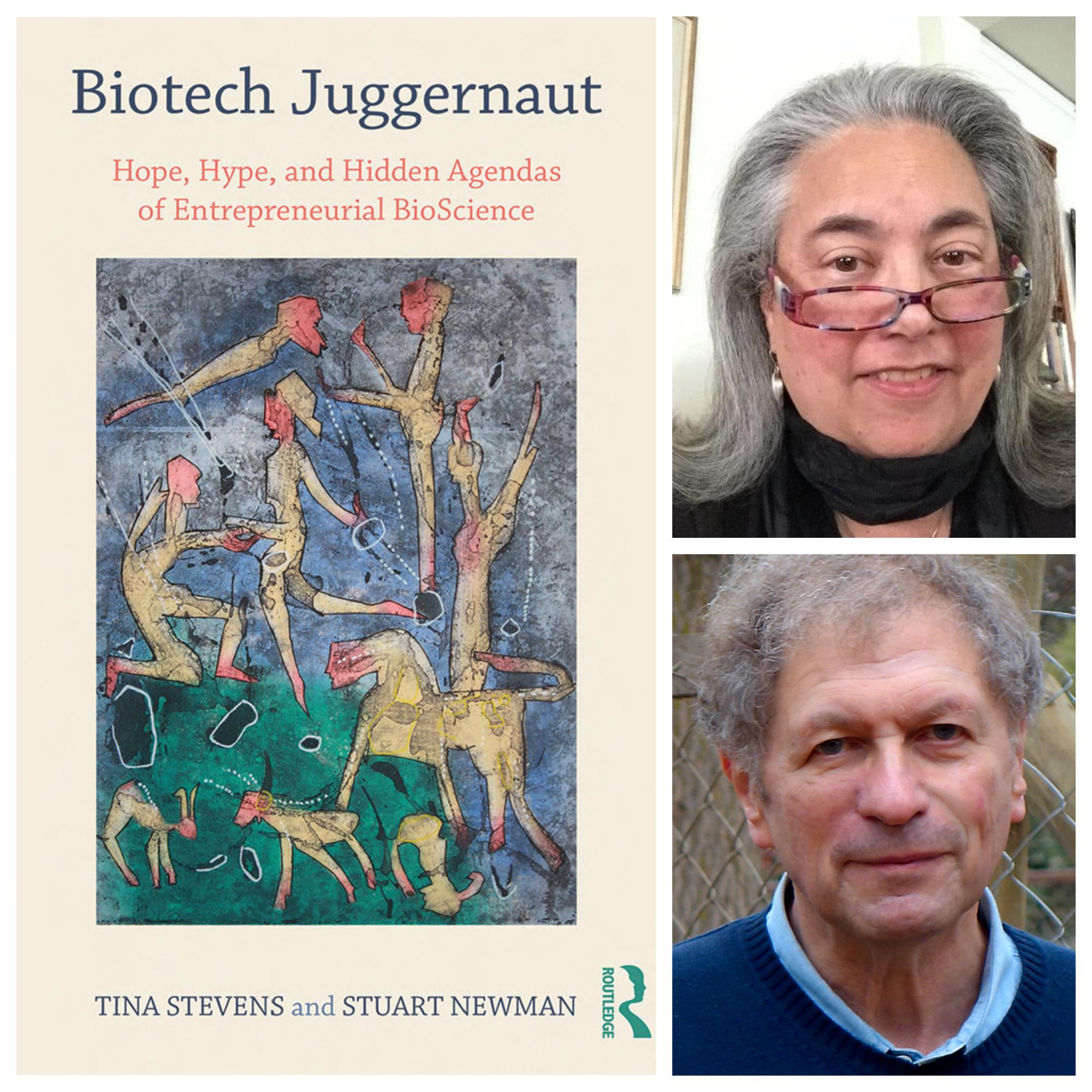

Biotech Juggernaut: Hope, Hype, and Hidden Agendas of Entrepreneurial BioScience (Routledge, 2019) documents the intensifying effort of bioentrepreneurs to apply genetic engineering technologies to the human species and to extend the commercial reach of synthetic biology. CGS spoke with authors Tina Stevens and Stuart Newman about the stories that led them to write Biotech Juggernaut and how they see this phenomenon playing out in 2019.

CGS supporters who contribute $200 or more will receive a copy of Biotech Juggernaut as a thank-you gift during our semi-annual fundraising campaign.

What compelled you to write Biotech Juggernaut?

Tina: The specific trigger was the 2004 California Stem Cell Research and Cures Initiative, a ballot measure known as Proposition 71. That’s when we experienced firsthand the political power of bioscience interests.

The backers of Prop 71 had an astonishing war chest of tens of millions of dollars to pay signature gatherers to get the initiative on the ballot and to flood the airwaves with ads, suggesting to voters that passing the initiative would lead to imminent cures. They also had money to bring legal action against the opponents of the initiative. Some pro-choice progressive colleagues and I were trying to make public the fact that one key type of embryonic stem cell research being prioritized by Prop 71 actually constituted a form of human cloning and required women’s eggs to do it.

The proponents’ lawsuit tried to prevent us from writing the rebuttal that would appear in the voter’s guide. And it’s at that point that I contacted Stuart. I had read about him and I knew that he had testified before Congress. He supplied an affidavit that helped us win the legal action—that is to say, we could go ahead and put the rebuttal in, although Prop 71 ultimately did pass.

The experience was revealing—that they could move so quickly to try to silence us. And my pro-choice progressive colleagues and me and Stuart and others saw that Prop 71—its passage—was the work of a juggernaut.

Stuart: When Tina approached me about the rebuttal to Prop 71 it wasn’t a totally new issue because ever since I was a graduate student, I had been involved in a kind of science critique. When I was training to be a scientist, I also taught myself to be critical about the abuses and misuses of science. I was exposed to the culture that produced the atomic bomb. I did my graduate work in physical science at the University of Chicago, at one of the main venues of the Manhattan Project a generation before. Among some of the senior people, there was a consciousness that science can be used for ill as well as good. Science for the People started there and elsewhere around Vietnam War-related uses of science and social misapplications of genetics, and I was involved in that.

Later, as a young faculty member, I co-founded the Council for Responsible Genetics, the first group that took on biotechnology as a new branch of science with potentially problematic applications. CRG began around the recombinant DNA debate. I could see then how ready some scientists were to distort scientific findings to serve what they saw as promoting science. They would minimize hazards and risks and downsides unwittingly and sometimes wittingly.

In the introduction to Biotech Juggernaut, you talk about “the dream of responsible science.” What would it take to make that dream of responsible science a reality? What changes would we need to see?

Stuart: Just like a lot of things, it would take a big change in society in general; I don’t think it can be partitioned off and solved on its own. As long as science is connected to business and gets funding based on its commercial viability it’s going to be distorted. Science and technology have improved a lot of things and helped a lot of people. They’ve also made a lot of people rich. For these reasons science has become a religion—and anybody who raises questions about it becomes a heretic. So, while individual greed plays a part, many tangible benefits have led to a very ingrained cultural disposition to privilege science and technology over many other—most other—human activities. With this has come a strong tendency to minimize its harms.

Tina: Within the last couple of weeks, scientists at Stanford University offered up what could be construed as their answer to your question. Stanford University cleared their researchers from any wrongdoing associated with the gene editing of twin infants in China. Dr. Quake knew about the widely condemned project, and Stanford concluded that he had observed the proper scientific protocol. How do you make sense of that? If Stanford considers Dr. Quake to have behaved responsibly, it means that Stanford considers a responsible scientist to be one who has an opinion about what constitutes an unethical project and chooses not to alert the public that he knows that this unethical project is about to take place. And, in fact, then informs his colleague who’s going to undertake the unethical project that he should proceed with “proper scientific practice.” How can one make sense of that? “Proceed ethically with the unethical.” It’s really kind of nonsense.

I think there are socially responsible scientists today. I just think it’s not easy in the current climate for them to speak out freely. And I think that’s a problem. But maybe things can change, and we can help them speak out.

How do you see the biotech juggernaut using language to influence the conversation around human germline modification?

Stuart: If you engineer an embryo and the embryo is at the stage where it has very few cells or just one cell, then all the cells in the body are going to be affected and it’s going to be passed on to future generations. So that’s why the term germline is used for that kind of modification. But the hazard from the point of view of scientists in my field—developmental biology—is not only the transmission to future generations. The main hazard, to me, is the harm that you’re doing to the individual who is engineered. Let’s say, theoretically, that you could perform the engineering so that the new gene stays out of the reproductive cells. A practitioner tells someone, “I’m going to engineer your future child. But don’t worry: If I make a mistake, it’s not going to be passed on to future generations.” While this would probably not be too reassuring to the prospective parent, for all the people who are criticizing germline genetic modification it would be fine because it doesn’t get passed on to future generations. That’s why I prefer to use the term “embryo gene modification” which includes germline transmission, but also potential harm to the child in question. Both of them are bad.

And how’s the juggernaut going to play out? Well, one of the ways that might play out is that a researcher might come up with a way of preventing a gene modification to an embryo from getting into the germline. This could be something that bioethicists and governmental panels could endorse. Bioentrepreneurs often play with words and concepts to promote their products. They would say, “Well, there’s no harm being passed on to future generations, so if a set of parents wants to take on that risk for their future child, well, that’s their right.” So, I think the main safety, philosophical, and cultural questions converge on the fact that people are proposing to engineer embryos, and that’s what should be stopped.

Tina: I think also that you can see the biotech juggernaut at play when they redefine things. One of the things that came up during the Prop 71 campaign is that they didn’t want to use the term cloning. Instead, they use somatic cell nuclear transfer. With respect to three-parent embryos, they talk about mitochondrial replacement. So that’s the biotech juggernaut at play.

Stuart: The three-parent procedure is a particularly egregious example because the deliberation process went on for about five years in Great Britain before it was approved. And all the while they were using mitochondrial replacement or mitochondrial donation, and it was never that. Even the bioethicists that were talking about it and the critics were all using mitochondrial replacement. But actually, it was only after it was approved by Parliament that journals like Nature started referring to it as nuclear transfer and some bioethicists started doing that as well. There may have been a lag time before the realization of what it was sunk in among the bioethicists. But the scientists knew it all along, and once they realized that people were on to the fact that it was a nuclear transfer, they really suppressed it until the approval was in place.

Can you explain the term bioentrepreneurialism and why is understanding this approach to market-based biotech advancement particularly important now during this time in our history?

Tina: Bioentrepreneurialism gets a big kickstart in 1980. That’s when you have the Chakrabarty v. Diamond decision handed down by the Supreme Court, and that’s the decision that permits patenting of bioengineered organisms. And then also in that year, Congress passed the Bayh-Dole Act, which allowed university researchers to privately patent bioproducts and processes that get funded by public money. Since then, university researchers and their promoters function in a professional environment where, more than ever before, scientific curiosity bends away from the instincts of basic research and “knowledge for knowledge sake,” and towards how to make applications that will enhance careers and build financial empires.

You see a lot of scientists who are Nobel Laureates or scientific researchers who also have their own biotech companies in the plural, but journalists don’t focus on that or don’t understand the implications of that. But there are definitely implications. And even those who may not have started their own biotech companies still operate in a professional culture where incentives and motivations and behaviors are shaped by the prospect of doing so. The conflicts of interest are apparent, I think. Another aspect of this is that the people who are doing the bioentrepreneurialism are also gatekeepers to the public information that’s necessary to understand that technology, and that also is a problem.

And why is it particularly important at this time? Because these processes are now affecting the human species, so it becomes even more urgent.

What do you say to critics who insist we don’t have to worry about eugenics or designer babies?

Stuart: Once the door is open, you can use it for anything people want to use it for. Some individual scientist can say, “I have no intention of using this for eugenic purposes.” But one person’s eugenics can be someone else’s “repair.” Who’s to judge? With mitochondrial procedures, originally the purpose was to prevent disease, but now it’s being used for infertility. Not exactly eugenics, but it’s mission creep—changing the use to make it more marketable. For some people, for example, lower-than-average height is an impairment, not just a variation; they will opt for increasing the height of their offspring and not call it eugenics. There’s really not a sharp line between curing disease condition and enhancing traits.

If you could elevate public understanding of one issue that you covered in your book, what would it be?

Tina: I hope our book elevates public understanding about those who are currently bearing the costs of marching toward Gattaca and those most hidden from public view right now—arguably, the young women who are being targeted for their eggs (eggs being the raw material needed for reproductive technologies). There’s really no adequate information about the long-term health risks for young women. And there’s reason to be concerned about that for the young fertile women undergoing the process. And, certainly, we’ve heard from young women who’ve suffered through the short-term risks, especially ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. I hope everyone reads the Congressional testimonies of the egg donors that we have in the book’s appendix and by the mother of one of these egg donors. But even though we don’t have adequate information, the pressure on young women to do this ratchets up with every passing year. The bioresearch and fertility industries keep coming back to the California Legislature seeking to legalize paying women for their eggs for research. Our Bodies Ourselves and others have been calling for a long time to track the long-term health of these young women; there’s no legitimate way for them to give meaningful informed consent.

Who do you hope reads this book?

Tina: Any and all beginners to these concerns. Especially young people. Hope for a human future lies mostly with them.

Stuart: I fully agree. I would like to see it in undergraduate or graduate courses on science policy and history of science. I also hope scientists and bioethicists will read it, but I’m not too optimistic about that.

Stuart Newman is a professor of cell biology and anatomy at New York Medical College and co-founder of the Council for Responsible Genetics. He is also co-author (with Gabor Forgacs) of Biological Physics of the Developing Embryo (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Tina Stevens is co-founder the Alliance for Humane Biotechnology and lecturer emerita in history at San Francisco State University. She is also the author of Bioethics in America: Origins and Cultural Politics (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Adrienne van der Valk is communications director at the Center for Genetics and Society.