WHEN Andres Moreno-Estrada began studying genetics back in the early 2000s, the high cost of sequencing DNA was the biggest barrier to understanding the role of genes in human health and disease. But with time, the problems shifted.

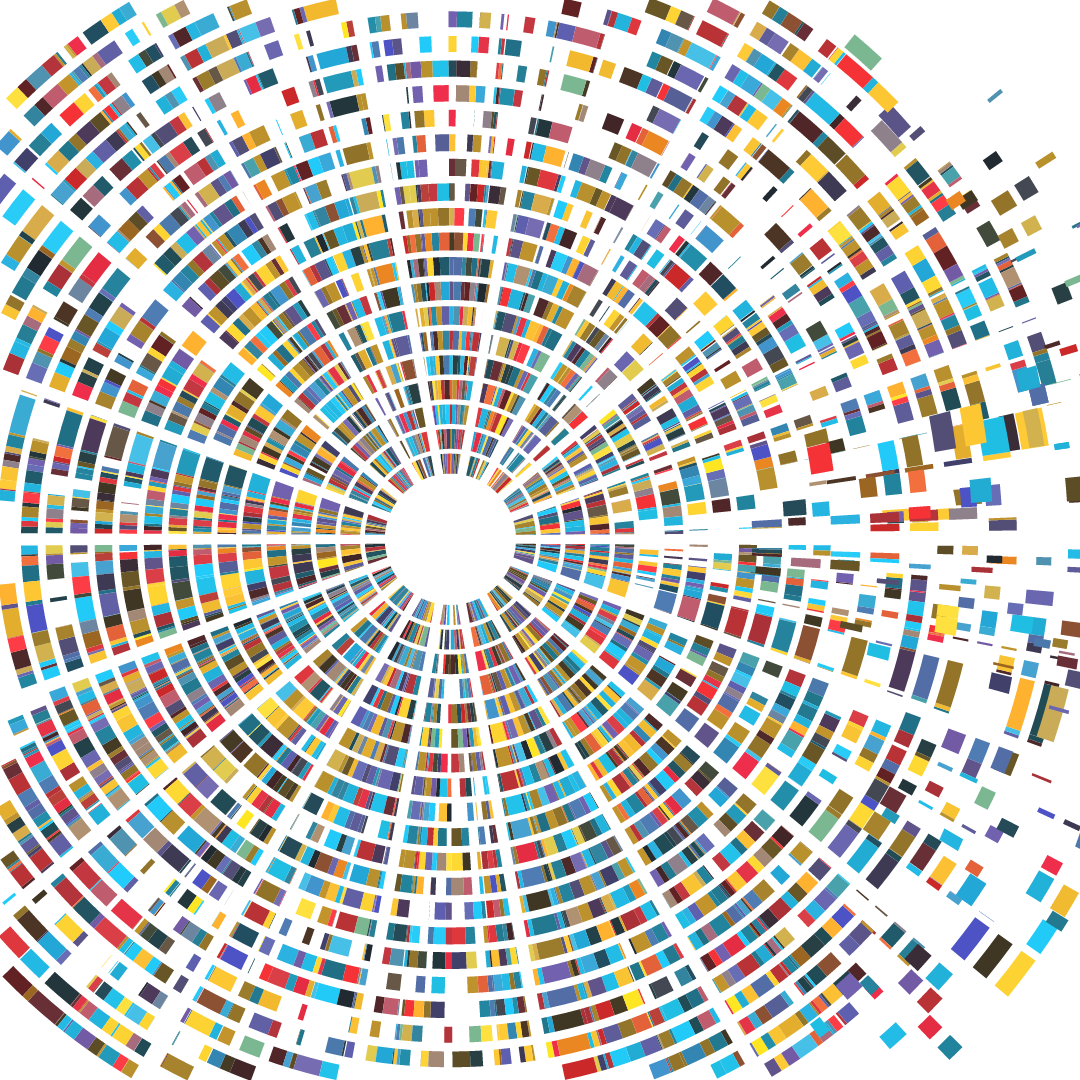

“Technology is no longer the limit,” said Moreno-Estrada, now a population geneticist at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity in Mexico. “Sequencing or getting genetic data is cheaper than before. The problem is in the unbalanced way this genetic information is being generated worldwide.” Researchers today rely on genetic data that’s disproportionately drawn from people with European ancestry, and mounting analyses suggest that their databases fail to capture the full scope of human genetic diversity. The result is a set of clinical tools that may not work as well for people whose ancestors lived outside of Europe.

Those issues are especially acute in Latin America, where new research suggests that more robust genetic data could allow physicians to better target certain medical treatments, especially for Indigenous groups.

At stake is the practice of precision or personalized medicine, which uses individual variability...